| Authors: | Tsanis, I. K. and Daliakopoulos, I. N. |

| Coordinating authors: | Tsanis, I. K. and Daliakopoulos, I. N. |

| Editor: | Brandt, C. J. |

| Source document: | Daliakopoulos, I. and Tsanis, I. (eds) 2014. Historical evolution of dryland ecosystems. CASCADE Project Deliverable 2.1. CASCADE Report 04. 126 pp. |

Description of the study site

General information

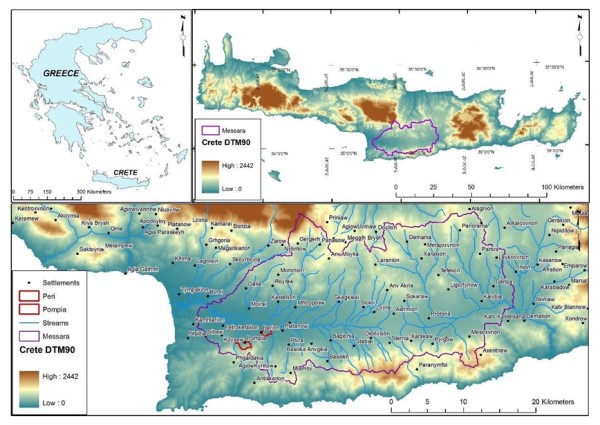

The Messara basin encompasses an area of 611 km² located in the central-south area of Crete, about 50 km south from the Prefecture capital, Heraklion, and constitutes the most important agricultural region of Crete. It is also the site for the Minoan palace of Phaistos and the Roman city of Gortys. The Messara Valley has remained rural with a small population of almost 45,000 inhabitants. In the Messara valley, the surrounding hills and mountains as well as elements such as Phaistos ruins, are strong landmarks, among the many that make Crete famous for its landscape and nature. Although human induced changes have affected the landscape, agriculture predominates in the area, thus being a staple to the local economy. The Messara Study Site for CASCADE is comprised of plots around the villages of Pompia and Perion.

Topography

Messara comprises of a plain with East-West orientation, about 25 km long and 5 km wide, with a total area of 112 km², hedged with mountains on the north and south sides. The basin can be conceptually divided in two hydrological catchments: the Geropotamos-Festos and the Anapodaris-Xarakas. The geomorphological relief is typical of a graben formation and the surface drops within 15 km from 2,454 m in Psiloritis Mountain to 45 m at Festos. The Geropotamos River with a westward direction and the Anapodaris River with an eastward direction drain the homonymous catchments. The catchment area of the northern slopes is 160 km² while the southern slopes constitute a catchment area of 126 km². To the north, the divide varies from 1,700 to 600 m from west to east, with the highest point being part of the Ida mountain range (peak at 2,540 m). The Asterousia mountain chain lies in the south and rises 600 m in the west to 1,200 m in the east. The Messara Valley covers an area of 398 km² within the watershed, with a mean altitude of 435 m. Charakas catchment lies at the east part of the Valley and Geropotamos River flows to the west, forming the catchment of Phaistos, where it meets a constriction at an outlet 30 m.

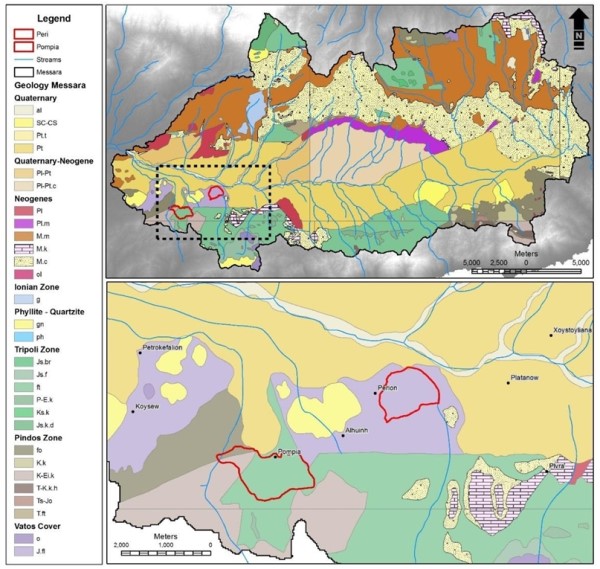

Geology and Soils

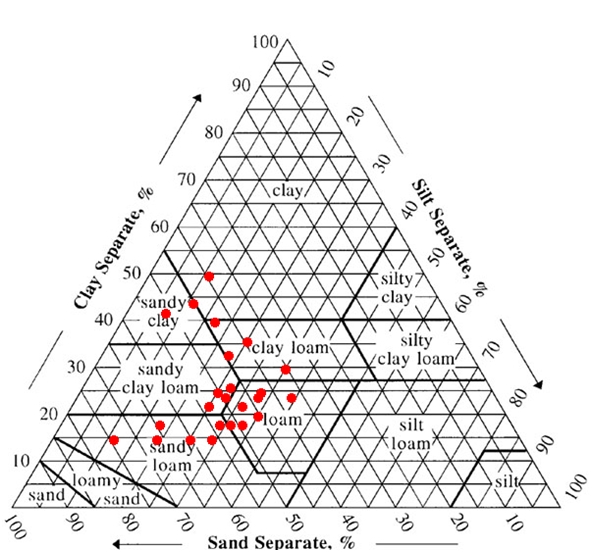

The plain area of the two catchments hosts the largest alluvium aquifer system of the island, with an area of 216 km². Topographically, the Messara basin is characterized by a flat basin morphology modified by river terraces and alluvial fans. The Messara valley, defined by the inner Messara graben zone, is an alluvial plain mainly composed of quartenary deposits. The plain is covered mainly by quarternary alluvial clays, silts, sands and gravels with thickness from a few meters to 100 m or more. The soils in the plain belong to the order of Entisols. In the north, the Valley is bordered by a hilly area of silty-marley Neogene formations, whereas in the south schist and limestone Mesozoic formations are dominant.

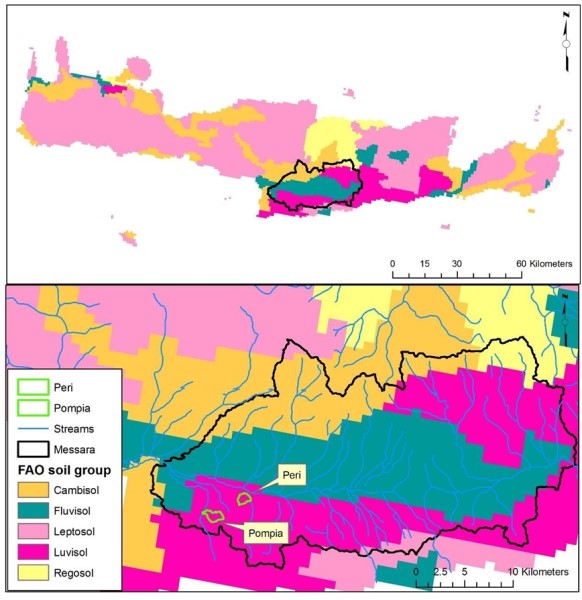

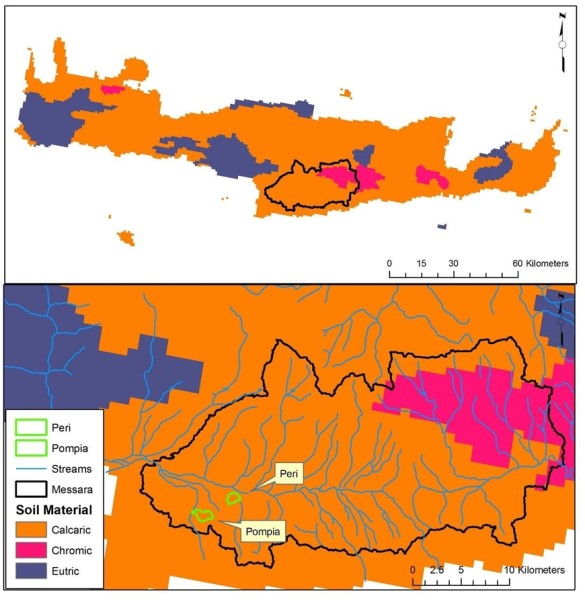

Dominant soils in the basin are cambisols (north slopes), luvisols (south and north-east slopes) and fluvisols (center of the valley). Calcaric soils are dominant across the basin with the exception of the east part where soils are chromic.

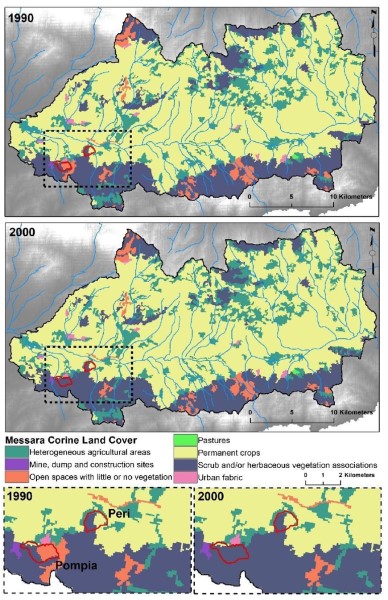

Land Use

About 250 km² of the total valley area of 398 km² are cultivated. The main land-use activity is olive growing (about 175 km²) with some grape vine cultivation (40 km²). The remainder of the cultivated land is used for vegetable, fruit and cereal-growing as well as for livestock grazing (higher grounds). The vines and about half of the land area under olives are drip-irrigated. For the period of 1984-1997 cereals covered an area of 25 km², vegetables 16 km² and grape vines 26 km², while the area of the watered olive trees increased from 38.5 km² in 1984 to 110 km² in 1997. The study site shows little change in terms of landuse since at least the 1940s. The only significant transition can be observed at the Pompia area, where “open spaces with little or no vegetation” actually represents burned area. From a total of 2.1 km², about 0.8 km² are within the Pompia Study Site and since then have been fully recovered and transformed to scrublands. Actually changes not clearly documented in CORINE include the intensity of exploitation for each landuse, as well as the extent of sealed and urban areas.

Climate

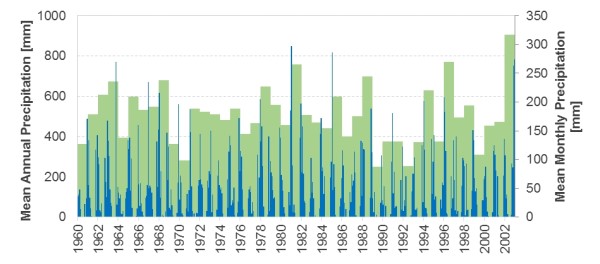

Messara Valley’s climate is classified as dry sub-humid and its hydrological year can be divided into a wet and dry season. Crete has a typical Mediterranean island environment with about 53% of the annual precipitation occurring in the winter, 23% during autumn and 20% during spring while there is negligible rainfall during summer. Although the Valley receives on average about 650 mm of rainfall per year, it is estimated that about 65% is lost to evapotranspiration, 10% as runoff to sea and only 25% goes to recharging the groundwater store. Rainfall increases with elevation from about 500 mm on the plain to about 800 mm on the basin slopes while on the Ida massif the annual precipitation is about 2,000 mm and on the Asterousian Mountains it reaches 1,100 mm. The maxima of mean monthly precipitation generally occur during winter with the exception of central south part of Crete (South of Messara Valley) where the maximum mean monthly precipitation is in November and September. For the available record, precipitation shows no significant trend over time and remains stable at an annual rate of 504 mm.

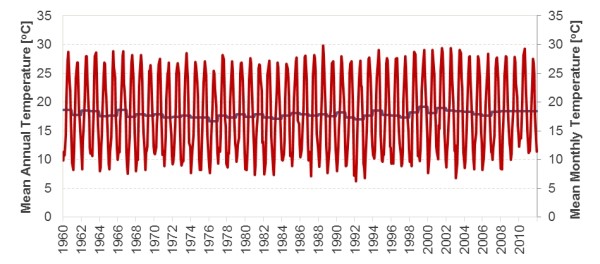

The average winter temperature is 12 ºC while in the summer it is estimated at 28 ºC. For the available record, temperature remains stable at an annual mean of 16.6 ºC. Relative humidity in winter is about 70% whereas in the summer it reaches about 60%. Pan evaporation is estimated at 1,500 ± 300 mm per year while the winds are mainly north-westerly. The potential evaporation in the area is estimated at 1,300 mm per year and for the study site it is estimated at 1,575 mm.

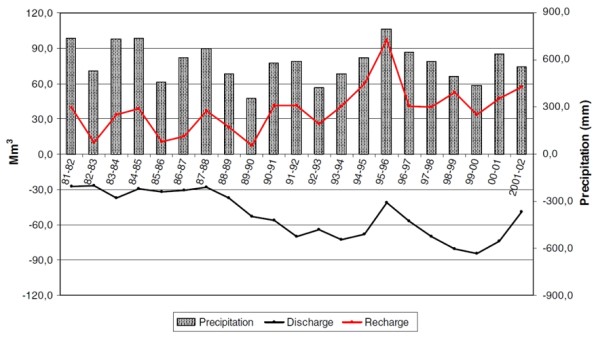

Hydrogeology

The plain area of the two catchments hosts the largest alluvial aquifer system of the island, containing several aquifers and aquicludes of complex distribution and properties. The inhomogeneity of the plain deposits gives rise to great variations in the hydrogeologic conditions even over short distances. Soil porosity decreases with depth below surface in a range of 0.05–0.13. The Neogene sediments and flysch are both characterized by a relatively high runoff while a small part of the mountain area is occupied by karstic formations characterized by negligible runoff and high infiltration. Groundwater is an important natural resource of the Messara Valley, as it is the main source of irrigation and domestic supply. Groundwater levels are highest in March or April with long recessions until recharge occurs in winter. Lateral groundwater outflow is small compared with the vertical groundwater outflow. In the area, 845 registered wells operated in 2004 and in 2007 their number was estimated at 1,400 causing a drop in the water table of as much as 45 m due to overexploitation. During wet years there is high recharge and low discharge, while the opposite occurs during dry years. It is also obvious that during the 1990s the discharge increased rapidly due to the intense groundwater withdrawal for irrigation purposes.

Water quality

Concentrations of physico-chemical parameters, heavy metals, conventional pollution parameters, total organic carbon and phenols as well as pH and electric conductivity values of karstic aquifer groundwater samples do not exceed the parametric values given by European Community. In shallow alluvial aquifers, water quality parameters, such as nitrate and sulphate, evidencing contamination sources such as fertilizers, wastewater disposal sites and olive-mill factories were estimated for groundwater samples contents over the drinking water guidelines given by Dir. 98/83/EC. Notwithstanding the fact that during the last 50 years pesticides were used in the area, only the aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) which is the major metabolite of glyphosate, was detected in the groundwater samples in values close to the parametric one. Finally, anthropogenic contamination due to agriculture, with high values of sulphate and chloride, was detected through the analysis of surface water (streamflow).

Flora

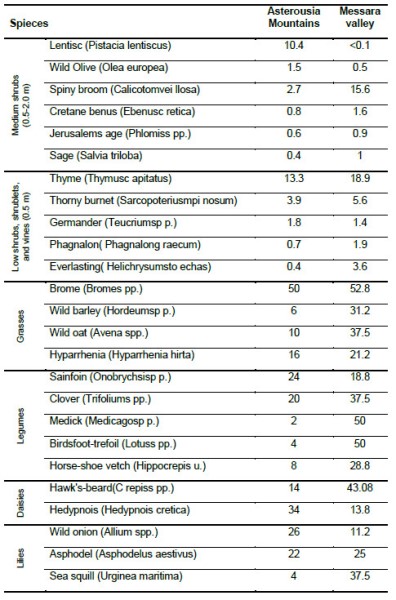

There is no doubt that with some exceptions, Crete was covered with forest before Neolithic times. Today, there is no forest left in the region but the natural landscape is dominated by scrublands, the typical Mediterranean garigue. The most common and most characteristic vegetation type in the area met today is the evergreen maquis/phrygana. It is found predominantly from 0 to 600 m, but may reach about 1,000 m. Two major units are recognized: a community with Pistacia lentiscus and Ceratonia siliqua is found in the lower zones and the coastal plains, always together with Olea europaea and Quercus coccifera,with Q. ilex, limited to altitudes between 300 and 1,000 m. As many natural species in the area provide free fodder, especially in overgrazed areas such as the study site, the less palatable / poisonous plants such as Urginea maritima often survive and dominate the landscape.

The Messara landscape has been in cultivation for thousands of years, leading to 30% of the flora of Crete being linked to agriculture and around 200 species being imported with agricultural systems from abroad. Two main agro-ecological zones occur in the region: the hilly zone, surrounding the plain, and the plain. Each zone displays different agro-ecological characteristics but also interacts with the other to the degree that it affects environmental variables such as water and fodder availability, soil preservation, fire hazard, etc. Since 1980, the marshes of the Messara valley have also been transformed to cultivated land.

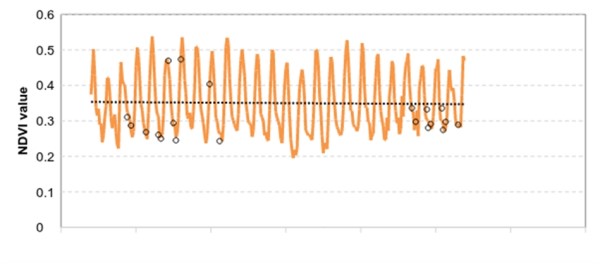

A synoptic view about vegetation health and the associated function of ecosystems can be derived from analysis of archival and on-going sequences of NDVI, an initial exploration of which has shown no significant trend since the 1980s.

Fauna

The fauna in Crete is the result of a severe human-induced selection in favour of species belonging to the geographic and cultural universe of the human groups that immigrated to the islands, within which domestic livestock predominate. Rational grazing, the model developed for several millennia in Crete, was harmonized with the local biodiversity and contributed to its protection by preventing abandonment. The cultivation of olive trees on agricultural lands (lowland areas of Crete) has resulted in the gradual destruction of the natural environment and biodiversity. Today, the fauna has 2,500 members 180 of which are endemic. The dominant pastoralism model regarding hilly - mountainous regions (foothills) involves free grazing of sheep and goats. Traditionally animals were grazing in the fields and in the olive groves and were used for transportation and land cultivation.

Studies on grazing-capacity (number of animals that can be supported per grazed area) are not available in Crete, thus causing pastoralists to increase herds to numbers that cannot be sustained by the pastures. When the nutritional needs of the animal population are not met, ultimately the shepherds are forced to deal with fodder costs. The use of fodder imported to Crete (mainly corn) forces animals to eat anything dry, as they have a cellulose deficiency, without which their digestion cannot be sustained. For this reason they are often forced to eat tree bark etc. to meet their nutritional needs, thus causing even greater damage to the natural vegetation.

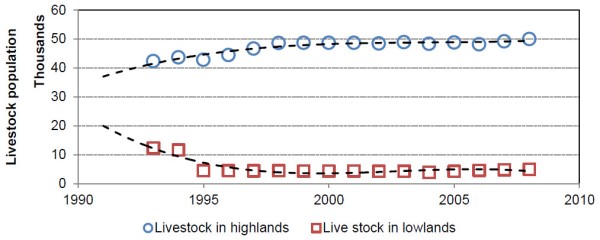

Animal population in Crete reached 2,200 million in 2000, and is now estimated to be around 1,700 million. In recent years (2007 to present), a 30% reduction of the animal population took place due to the doubling of the fodder price. On average, each producer has about 200-250 animals of which about 20% are goats. Livestock population in lowland, more urbanized and more touristically attractive areas is decreasing while highland population is increasing. In recent years, chances in livestock population are marginal.

Vegetation – soil system

The selected vegetation in the study site is Hyparrhenia hirta which is native to much of Africa, the Mediterranean and Eurasia. The plant is a densely tufted, annual, or more usually perennial, grass, 0.3–1.5 m tall with awned, hairy, grey green spikelets carried in many pairs of racemes, in an open panicle and tough, dense bases sprouting from rhizomes. Each raceme has a leaf-like bract at the base and the inflorescence atop the wiry stem is a panicle of hairy spikelets with bent awns up to 3.5 cm long. The grass can grow in a variety of habitat types, in dry conditions, heavy, rocky, eroded soils, and disturbed areas. It grows on a wide range of soils from shallow sands to clays and floodplains, clay soils, dolerite hills, disturbed and shallow soils. Grasses like Hyparrhenia hirta show a marked increase in flowering after fire events, but the herbaceous species are soon replaced by woody plants. Coolati grass is a C4, usually perennial plant, however under good nitrogen conditions and in a Mediterranean environment it is not expected to be more productive than the cool season C3 plants. Along a transect across the Western Messara, the average percentage frequency of Hyparrhenia is 16.0% and 21.2% at Asterousias Mountains and Messara Valley, respectively.

The soil in the study site is of average composition and is characterized as loamy and calcareous. It contains 30-50% CaCO3 and moderate to low organic matter (0.8-1.2%). pH is neutral to slightly alkaline, between 7.6 and 8.5. This soil belongs to Luvisol. The mixed mineralogy, high nutrient content and good drainage of these soils make them suitable for a wide range of agriculture, from grains to orchards to vineyards. Luvisols form on flat or gently sloping landscapes under climatic regimes that range from cool temperate to warm Mediterranean.

Socioeconomic status

The agricultural lands in the mountains of Greece are characterized by a decreasing population density due to socio-economic and political factors. This land abandonment, as a result of outmigration and off-farm employment, leads to less productive lands that are susceptible to environmental degradation. In Messara, fields are usually scattered around the villages with the average farmer owning about 5-10 plots with an average farm size of 3.5 ha, while the average distance between the village and the plots is 3-5 km. This unprofitable system that obliges farmers to commute partly exists due to the Cretan heritage system, according to which all children receive a part of the farm, and partly due to the unwillingness to exchange fields. The island customs discourage land consolidation thereby leading to increased fragmentation and declining farm size. This custom can explain the high number of small land-parcels prevailing in the study area. Furthermore, most grazing grounds are not clearly defined as they can be both private and public and many make use of the law about acquisitive prescription allowing them to take ownership of land after 20 years of undisputed use. Both land tenure and taxation system appear to play an important role in the farm size. The cultural value system dictates maintaining the land ownership even during the absence of the owners who often return to cultivate them after retirement.

Nowadays, Cretan agricultural practices mainly include monocultures, with olive groves and vines both in the hills and in the plain. Vine growing has become quite challenging, as it comprises intensive labour in contrast with the low prices in the market. Although excellent wines and raisins are produced, harsh global market competition, management and marketing problems, as well as the current economic crisis, cause profits to reduce significantly. Furthermore, olive oil is the main product of the island and at the moment the most profitable crop of the agricultural sector. In contrast to fresh products, olive oil does not need fast transport, but its price is also lowered on the saturated European market under the pressure of economic crisis while marketing problems have started to appear as well. This single-commodity approach makes olive growers vulnerable to market fluctuations. Economic crisis and the inability of pastoralists to purchase fodder have resulted in the abandonment of pastures and as a result the problem of overgrazing is indirectly solved with adverse effects.

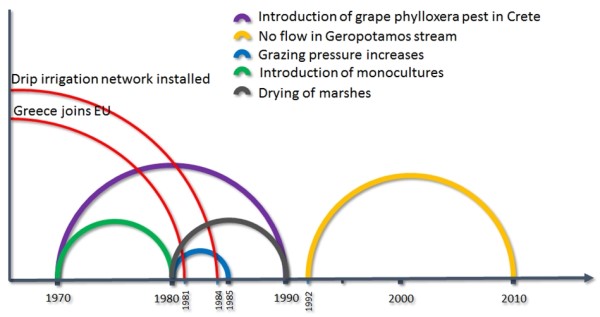

Timeline of events

A brief event timeline shows the most important changes and milestones that occurred in the natural and social environment of Messara basin.

Main Causes of Land Degradation

Human induced Drivers

Agricultural policy and excessive withdrawal of water: In Crete, as in the rest of Greece, high profitability of irrigated farming has led to over-exploitation of water resources. The amount of water allocated for irrigation is estimated to be 82% of the total consumption. In general, water consumption has increased by more than 4% per year. Most of the total water consumption is used in agriculture for the irrigation of olive groves, vineyards and vegetables and the European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has significantly affected cropland areas and land use types. In Crete, many marginal areas under natural vegetation were cleared and olive groves have been planted. These areas become particularly vulnerable to erosion due to inadequate soil protection and reduction of infiltration rates which follows loss of organic matter content and soil structure decline. Widespread olive production in steep hilly areas in combination with the lack of water and grazing has resulted in desertification problems.

The main source of irrigation water in Messara is groundwater as there is little surface water flow outside the winter months. Groundwater is the key resource controlling the economic development of the region, and it comprises a component of the environment under siege as water demand is increasing with time. The increased demand of water, either for domestic or agricultural use, cannot always be met, despite adequate precipitation. Water imbalance is often experienced, due to temporal and spatial variations of precipitation, increased water demand during summer months and the difficulty of transporting water due to the mountainous areas. A characteristic example of groundwater over-exploitation is the western part of Messara Valley. Lately, there have been growing concerns over the possible depletion or deterioration of the groundwater quality in the basin due to intensive pumping beyond the safe yield of the basin.

In 1970, two irrigation systems were constructed in the area as prototypes for a future extensive network. At the time, the average groundwater level fluctuation over the hydrological year was about 3 m, which for a mean porosity of 0.05 for the clayey phreatic aquifer of the Valley gives an average recharge of 150 mm per year. Measurements have shown that the groundwater level at that time was about 5 m below surface and the maximum rate of withdrawal was 5 Mm3 per year with discharge rates as high as 300 m³/h. Then, the average surface discharge out of the Valley was 20 Mm³ per year which corresponds to a loss as runoff about 50 mm per year.

In 1984 an extensive network of groundwater pumping stations was established in Messara Valley, causing an increase in the rate of groundwater withdrawal and a dramatic drop in the groundwater level of about 20 m. Since the groundwater irrigation network was installed, the groundwater level has on average decreased by about 2 m per year as what used to be non-irrigated cultivation of vines and olive trees was transformed to drip-irrigated cultivation. The end effect is that about 660 mm of water per year, or about an average 2 mm per day, is lost from the Valley (Vardavas et al., 1997). Although the amount of water required for irrigation of olive plantations is relatively low compared to arable crops, there has been a dramatic over-exploitation of aquifers accompanied by water quality deterioration. In addition, regional development, infrastructure, spatial planning policies and the implementation of Integrated Mediterranean Programmes constitute the factors that have considerably affected the exploitation of natural resources. Finally, the sequential occurrence of dry years in the 1990s has led to more intensive pumping to meet the irrigation demands. As a result, in 2000 the groundwater level was 45 m below the surface. During the last three years, the runoff of the Geropotamos River is close to zero due to the percolation rate increase.

Overgrazing: Free-range livestock can, over time, degrade rangelands due to overgrazing. The rate of degradation depends on the density of the livestock population and the restoration rate of the natural flora. The relationship of those rates can be used as a tipping point index. The direct effects of the introduction of domestic grazers on native faunas since prehistoric times are well described for the Mediterranean islands, where original faunas have been affected by species extinction and introductions promoted by humans. The Asteroussia and Psiloriti mountains of Crete represent characteristic cases of degradation caused by intensive grazing and fires set by shepherds. Soil erosion is apparent in many cases, and areas that appear irreversibly degraded (desertified) are often found. The grazing areas of the Psiloriti Mountains in central Crete extend into higher altitudes of sub-humid and humid Mediterranean climates (1,000-2,000 m). In areas often covered with matorral or mountainous phrygana, relict kermes oak forests (Quercus coccifera) are still found. Moreover, in this region grazing pressure has significantly increased. Statistical figures for some of the mountainous communities show an increase of the total number of sheep and goats by more than 200% between 1980 and 1990. Nevertheless, it has been observed that flora biodiversity can be fully restored by applying rational grazing on degraded areas when fertilization and fence application for at least a month take place. The implementation of such a program requires the removal of animals for a period of 2-3 years, after which the site can be grazed at carrying capacity.

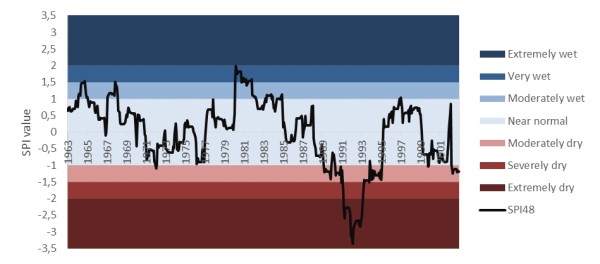

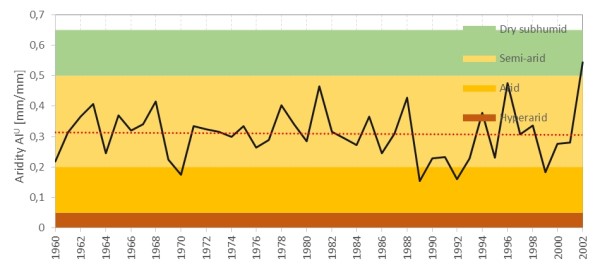

Natural Drivers

No prolonged drought events have taken place throughout the available record and the area is mostly under normal conditions. Nevertheless, especially extreme drought conditions took place in the years 1992–93. Drought phenomena under mild conditions were also observed during the period 2000–02. The sensitivity of drought to the precipitation variability rather than the long term average is depicted in the SPI results. Regarding the Aridity Index, the area displays stability with a slight decreasing trend. This long term trend might have been significant but was overturned by the relatively large precipitation amount received in 2002 (905 mm). The area generally belongs to the semi-arid bracket with only four years crossing over to a more arid character. Nevertheless, this tendency to arid climate is possibly occurring at a higher frequency after the 1980s.

Indirect causes

Greece joined the EEC (European Economic Community) in 1981 and Greek agriculture became subject to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Up until 1992, the aim of the CAP was to increase production, and to provide cheap rural products accompanied by reasonable rural incomes. The consequences of the CAP in Greece were the intensification of agricultural production, extensive mechanisation of crop production, creation of monocultures, such as cotton and olive trees, large surpluses of some products, the disappearance of some unique Greek plant varieties which were replaced by hybrids, and the loss of the rural balance with its self-sufficiency in agricultural products. Greek farmers have re-orientated crop production towards the globalised market and Greek agriculture is no longer based solely on the needs of the country or the European Union. This has resulted in the orientation of Greek agriculture to three main crops: olives, cotton and tobacco. As a result, the country has simultaneously lost its self-sufficiency in products such as cereals, fruits, and vegetables. Crete has not been an exception to this.

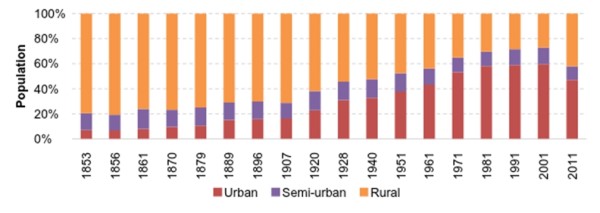

Rural migration has also had a significant impact on cropland and land management practices. Large scale migration from rural to urban areas took place in Greece after the 1950s and since then rural population has continued to decrease. As a result, land was either abandoned or rented. These conditions facilitated the over-exploitation of rural land from the few remaining farmers who often adopted harsh methods, such as uncontrolled burning of shrubs, otherwise condemned by neighboring users. At the same time, the total population of Crete has increased in the last four decades. The rate of increase was especially high in the area of Heraklion, putting significant pressure on land for transformation from agriculture to residential or industrial uses. Apart from urbanization, mass tourism has also put a pressure on the Cretan landscape in the last few decades. The total number of tourists in Crete exceeds 2 million per year and this number may double by 2025. As a result and a means to improve their financial profile, in less productive areas, particularly along the coast, farmers have sold their land to developers for the construction of tourist infrastructure.

The CAP, through its structural policies, supported an adequate income to farmers, contributing to the development of regional economies and reform of landscapes, particularly in less favoured areas. In addition, subsidies allocated under the CAP accelerated the intensification and specialization process in agriculture. Subsidies, allocated based on the area cultivated encouraged farmers to keep highly degraded land under cultivation, or to expand cultivation into marginal areas, even with low crop yields, thus accelerating erosion and land degradation. On the other hand, the lack of coordination between organizations (development agencies) and state services responsible for land management as well as knowledge gaps, have been liable for the lack of Cretan landscape policy application. Organized efforts from the EU strive to bridge these shortcomings in management, infrastructure and knowhow but there is still a long way ahead.