Introduction

Whether an ecosystem moves towards a shift is determined by its ecological dynamics in interaction with the management of the land. The previous sections of this paper have shown how we can assess ecosystem shifts and which soil characteristics and plant processes facilitate or prevent such shifts. When it comes to the question on how to change the management in order to prevent a shift, mitigate or rehabilitate land degradation, we thus need to understand this interaction of management and ecology. The social-ecological systems and their spatial and temporal dynamics determine the demand for ecosystem services, which again determine how the land is managed. This requires the integration of users’ perspectives. In CASCADE, stakeholders such as land users, land planners and policy makers were engaged in the research right from the beginning in order to better understand how vulnerable ecosystems can be managed. Although generalizing impacts of land management remains challenging, as practices can be extremely diverse depending on the area, actors and timing (Schwilch et al. 2014), with CASCADE we were able to advance by elaborating some principles for three typical Mediterranean dryland drivers of degradation: forest fire, overgrazing and land abandonment.

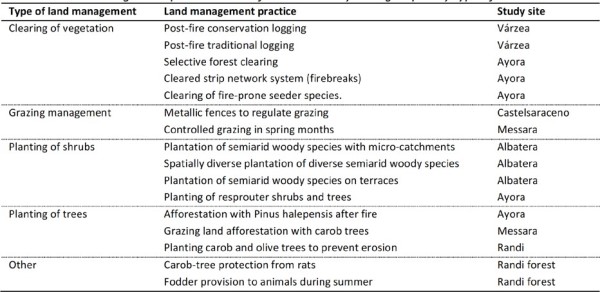

Almost all the practices assessed (Table 2) have an overall positive impact on the resilience of the land management systems in which they are implemented. However, three quarters have at least some negative impacts (Jucker et al – under review). In general, the higher the number of disturbances affecting a system, the less positive the contribution of land management practices to resilience. With the exception of the clearing of fire-prone species in Ayora, no other technology has an all-round positive effect. Thus, combining different land management practices appears to be the best strategy to consistently increase resilience against all disturbances.

Table 2: Land management practices identified in the study sites grouped by type of intervention.

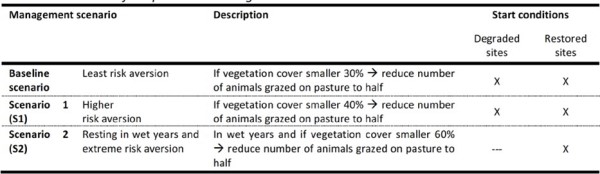

Table 3: Scenarios of adaptive land management.

Forest fire context

Our results stress the importance of preventive actions before a fire event (Jucker et al 2016). Among the land management practices that can be implemented before the fire, fuel management appeared to increase forest resilience the most. Fuel management means minimizing fuel load and connectivity in order to reduce fire risk (e.g. by reducing highly flammable biomass and creating bare strips). Management of forest regeneration (after fire) and reforestations should promote a low density, spatially differentiated and species-diverse canopy, which also reduces outbreaks of pests. While forest regeneration from seed banks is only possible with long time intervals between fires, regeneration from resprouting individuals fosters a quick recovery, especially under beneficial conditions such as north-facing and rather gentle slopes (Jucker et al. 2016). CASCADE studies have also highlighted that establishing a vegetation cover immediately after fire has an important role in preventing soil erosion and thus retaining nutrients and maintaining soil fertility (Mayor et al 2016). Mulching has been shown to be an effective practice to prevent soil erosion when there is lack of spontaneous cover, also in fire breaks. To control the fuel load and the risk of spreading pests and diseases, a vegetation cover of 50-60% has been shown to be most effective.

In Várzea, restoration actions (post-fire logging) improved ecosystem services at the very short term (< 2 years) after their implementation although the dynamics of the plant communities were slowed down, probably due to the impact of the heavy machinery on the earliest regenerated plants. In Ayora, where the ecosystem service assessment was conducted more than ten years after the application of restoration actions, positive impacts on most properties and services were observed, especially on biodiversity and fire risk reduction. Only C sequestration was negatively affected by restoration as actions included the removal of seeder fire-prone vegetation and hence the aboveground biomass.

Overgrazing context

Promising management practices to control vegetation cover include rotational grazing, fodder provision and area closure. In Randi and in the overgrazed state in Castelsaraceno we observed a general improvement of ecosystem services by grazing exclusion, especially in Randi where plant cover, litter accumulation and aboveground biomass recovered to similar levels found in the undisturbed reference areas. However, grazing exclusion, if economically possible at all, can also lead to shrub encroachment, increased fire hazard and reduced fodder value, as found in Castelsaraceno, implying that management during recovery is necessary.

Restoration in Messara aimed to transform land use from grazing to carob tree orchards as a silvo- pastoral system rather than to recover the pre-disturbance state of the ecosystem. This practice has proved to provide multiple benefits such as additional fodder and shade for animals, decreased soil erosion, improved soil fertility and additional income through olive and carob products. The grazing systems in Randi and Castelsaraceno are affected by animal pests (rats, boars), which are mitigated by short term management options like tree protection and pasture fencing, but would require an integrated ecosystem approach to promote natural predators. Another problem is pasture degradation by more perennial, invasive and/or unpalatable species or thorny shrubs, influenced by grazing intensity, animal types and herd composition. Beside diversifying herds, options include manuring pastures, seeding fodder species and mechanically removing thorny shrubs. Controlled grazing as well as avoiding abandonment also reduces risk of fires. Once a fire has occurred on grazing land, it is important to allow a minimum of 2 years for resting (while providing supplementary fodder) or actively revegetate, in order to prevent a regime shift. Remaining plant individuals can be used as nurses to increase the recruitment of seedlings planted below.

Land abandonment context

In the Mediterranean, land abandonment is widespread. Land management options for abandoned land include revegetation, rotational grazing or alternative uses of land, such as bee-keeping, biodiversity management, tourism or wind / solar energy production. It also needs to be considered that land, which is not used economically at present, can become valuable in future and thus knowledge and infrastructure might need to be maintained. Cooperation and new forms of management (e.g. silvi-culture) help to overcome labour availability constraints.

Act in time: Guiding land managers and policy implications

Looking at stakeholders’ perception of the past activities in response to regime changes, environmental management adaptation measures were the main interventions across all study sites (67% of measures across sites). Socio-political measures formed the next largest set of actions (15%) and consisted of improving land use and environmental management through cross-sector organization, advancing or creating policies for land use, and patrolling to prevent illegal practices. Under socio-economic measures, stakeholders mentioned economic support, subsidies, and migration.

By complementing the ecological assessment of the rangeland resilience model with insights on investment costs (e.g. costs to purchase supplementary fodder) and income through livestock production we assessed scenarios of adaptive land management representing varying levels of risk aversion and resting periods as a conservational strategy (Tab. 3). In this modelling approach, we distinguished degraded and restored starting conditions and particularly considered the emergence of windows of opportunities and risks to capture critical land management timings that realize ecological benefits at minimum risk and cost (Sietz et al. 2017). Our findings show that the socio-ecological effectiveness of these management scenarios differed largely according to windows of opportunities and risks, starting conditions and investment and capital costs (e.g. for supplementary fodder and hired labour). For example, the higher risk aversion and resting in wet years/extreme risk aversion scenarios (see S1 and S2; Tab. 3) implied a significant increase in the likelihood of maintaining a vegetation cover above 40%, though only at restored sites. Yet although the conservational scenario S2 effectively prevented degradation, the economic loss was greater (-370Euro/ha) than in S1 (- 140Euro/ha). This indicated that policy incentives such as subsidies would be useful to increase land users’ motivation to implement this type of management.

Besides scenario analysis, monitoring of key processes and adaptive management are essential for decision making and inherently linked to resilience thinking. In particular, increased response diversity is crucial to better manage critical dynamics and emerging opportunities and risks and thus build resilience to future socio-ecological disturbances. The variety of promising measures within the CASCADE study sites and the information about their sustainability and resilience was used as the basis for guiding natural resource managers in improving the management of dryland ecosystems, in particular with regards to preventing disturbances, mitigating their negative impact and ensuring recovery. With this, land management takes an important role in avoiding ecosystem shifts to degraded states. Three booklets on the three above-mentioned prevailing Mediterranean dryland drivers were produced (see Schwilch et al, 2016). Each booklet has a number of ecological principles and related land management recommendations, each taking into account that ecosystems are also affected by the occurrence of droughts, as the impact of the driver may vary depending on drought conditions.

Decision making regarding SLM and the prioritization of measures requires stakeholder engagement at every stage of the process, as stakeholders have diverse views and hold different priorities. Stakeholders recognize the benefits of strong law enforcement and decision making in SLM, however, different stakeholders mentioned diverse levels of autonomy and state intervention as being desirable. Measures for fire prevention and environmental conservation need to consider short term and long- term consequences for land users, to avoid disengagement and land abandonment. Incentives and strategies to prevent land abandonment need to be in place in order to develop a comprehensive strategy that includes social, cultural and economic considerations. Particular factors that need to be considered include the re-valorisation of rural practices, incentives and support to new generations in the form of education and financing, and the formation of cooperatives and other communal efforts.

Discussion and conclusions

The management of vulnerable ecosystems is a challenging task. This includes maintaining or enhancing the natural resource base as well as sustaining productivity. It requires the maintenance and restoration of vital ecosystem components that provide resilience to climate change, disasters and other threats and risks. In this way, sudden shifts might be prevented. Cost-effective management interventions, acceptable to stakeholders, should thus be applied before thresholds are reached, or when windows of opportunity occur. By considering investment costs together with expected benefits and windows of opportunities and risks, CASCADE findings advance our understanding of socio- ecological determinants of specific land use strategies (Sietz and Van Dijk, 2015) and the evaluation of threshold behaviour. These insights can facilitate land-based management decisions aimed at addressing heterogeneity in global sustainability challenges such as loss of biosphere integrity, livelihood insecurity and vulnerability.

CASCADE provided two key lessons for managing vulnerable ecosystems in cost-effective and efficient ways. These are

- the need for reliably predicting windows of opportunities and risks linked with SLM and restoration advice tailored to land users’ needs and

- managerial flexibility enabling continuous and rapid adaptation of management decisions according to emerging opportunities or risks.

Interventions should include bundles of different practices used in combination to both mitigate the pressure and reduce vulnerability, and be supported by policy. Only if we manage to effectively avoid ecosystem shifts, reduce land degradation and reverse the negative consequences of both, we will be able to contribute to a land degradation neutral world and as such to SDG 15.3.